In 1897 the Nordeutscher Lloyd ship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse took the Blue Riband from Cunard's Campania and Lucania. Thereafter German ships held the trophy without challenge. It was not until 1902 that negotiations began between the Government and Cunard with a view to building two superliners, the Lusitania and Mauretania, capable of winning back and holding the Blue Riband for Britain. By 1903 an agreement had been reached whereby the government would lend £2,600,000 to Cunard to build two ships capable of 24 to 25 knots. In addition they agreed to make an annual payment to Cunard on the condition that the two ships were capable of being armed and that the Government would have a claim on their services in times of national emergency.

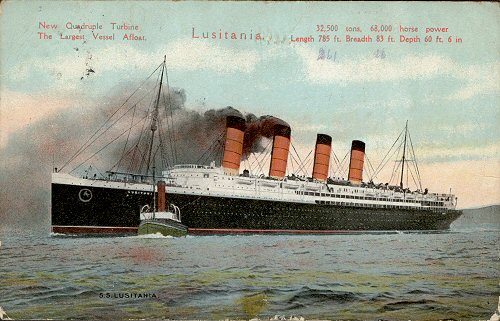

In an effort to ensure the speed requirements were met, Lord Inverclyde, then chairman of Cunard, chaired a committee of experienced engineers to discuss the subject in September 1903. In March 1904 the committee decided to utilise turbines, as opposed to reciprocating engines. Another problem was the hull design and size of the two new ships. After a series of private experiments and tests by Dr.R.Froude in the Admiralty tank at Haslar near Portsmouth this problem was resolved. It was decided that the two new ships would be 785 feet long and have gross tonnage of 32,000.

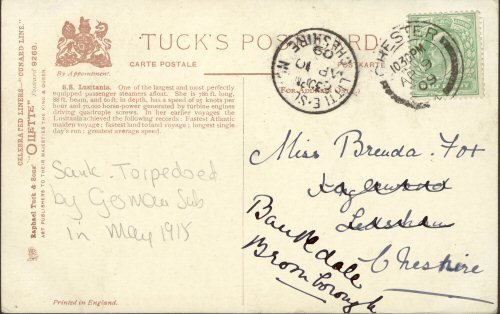

The contract for the building of the Lusitania went to John Brown & Co Ltd of Glasgow and the keel was laid in May 1905. The ship was launched on 7 June 1906 by Lady Inverclyde. The Lusitania was the largest vessel afloat at the time and had seven decks for the use of passengers, who enjoyed the palatial accommodation. Third class passengers were no longer accommodated in 'open berths' but in four- or six-berth cabins. The machinery also marked the Lusitania as a pioneer in maritime history. The ship's quadruple-screw propulsion unit was driven by direct-drive steam turbines which developed some 68,000 IHP and, revolving at 180 rpm, were capable of driving the Lusitania at 25 knots. The fact that the ship's coal bunkers ran along the sides of the boiler rooms was also unconventional. This afforded some protection to these vital machinery spaces, as they were below the waterline and vulnerable to damage caused by collisions or enemy action. It was the latter, perhaps, that was foremost in the minds of the planners for in times of war the Lusitania was intended to be converted into an armed merchant cruiser. To this end it was designed to carry 12 quick-firing 6 inch guns.

After trials in the Clyde the Lusitania left Liverpool on 7 September 1907 on its maiden voyage to Queenstown and New York. It was estimated that over 200,000 people gathered to witness the ship's departure. Despite obvious attempts to regain the Blue Riband from the German ship, Deutschland, the Lusitania did not manage this until its second outward voyage on 5 October 1907. It made the Queenstown to Sandy Hook crossing in 4 days 19 hours and 52 minutes. In November 1907 the Lusitania's sister ship, the Mauretania, came into service and it was not long before the slightly better performance of the latter began to show.

In June 1908 the ship's outer propellers were replaced with improved versions and in November Captain William Turner was appointed to command the Lusitania. He was a Liverpool man who first went to sea when he was just 13 on board the sailing ship White Star. He joined Cunard in 1878 and was holder of the Humane Society's silver medal for saving life at sea. During his career he served on the Cherbourg, Umbria, Carpathia, Ivernia and Caronia. Soon, in February 1909, the ship was fitted with new four-bladed propellers.

After a bad period, during which the ship had problems such as damaged propeller blades and damaged turbines, the Lusitania broke its last speed record in March 1914 on a voyage from New York to Liverpool. The outbreak of World War One meant that the role of the ship was about to change. Upon arrival in the Mersey the Admiralty decided that they did not need the ship as an armed merchant cruiser but they paid for the ship to remain at Liverpool at their disposal. The Lusitania made two trips between Liverpool and New York during October 1914 and then began a monthly service on this route. In order to save on coal and labour six of the ship's boilers were closed down and its maximum speed reduced to 21 knots.

On a voyage leaving Liverpool on 16 January 1915 the Lusitania was involved in an international incident which gave the ship's presence in the North Atlantic a very high profile. The ship was travelling through rough seas on the way to Queenstown and, fearing the possibility of a torpedo attack, the Captain hoisted the 'stars and stripes'. With America still neutral Germany was reluctant to bring her into the war on the side of the Allies, so it was considered that this would guarantee a safe passage. The use of the US flag, however, came to the notice of the press and the incident made world news. Soon, in April 1915, the German embassy in Washington sent warnings to the newspapers in New York to the effect that the passengers travelling on Allied ships did so at their own risk.

For its 17 April voyage from Liverpool the Lusitania was commanded by Captain William Turner, who relieved Captain Dow when he went on leave. It made its final sailing from Pier 54 in New York on 1 May 1915, with some 1,959 passengers on board, amongst whom were the usual sprinkling of famous and wealthy. The cargo was entered on the manifest as foodstuffs, metal rods, ingots and boxes of cartridges. Controversy about the true nature of the cargo would persist for many years.

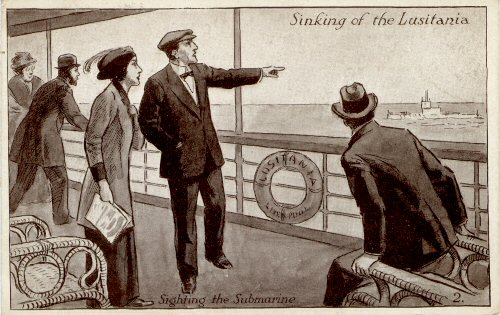

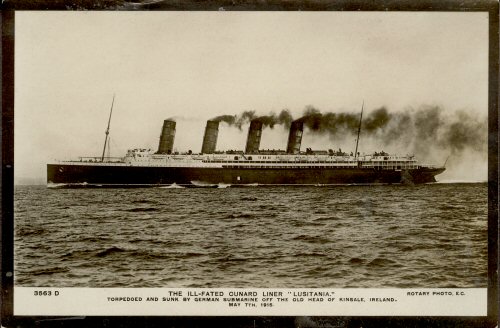

By 7 May the ship had entered what was called the danger zone, waters in which enemy submarines might be expected. Captain Turner took all possible precautions ordering all the lifeboats to be swung out, all the bulkhead doors to be closed, look-outs to be doubled and steam pressure to be kept high to give the ship all possible speed in case of emergency. At 8.00am speed was reduced to 18 knots to secure the ship's arrival at the bar outside Liverpool at 4.00am the following day, in order to catch the high tide. At 12.40pm the ships course was altered in order to make a better landfall. The ship was brought closer to land and the Old Head of Kinsale was sighted at 1.40pm. Having steadied the ship on this course an officer began to make a four-point bearing at 1.50pm, but this was never completed.

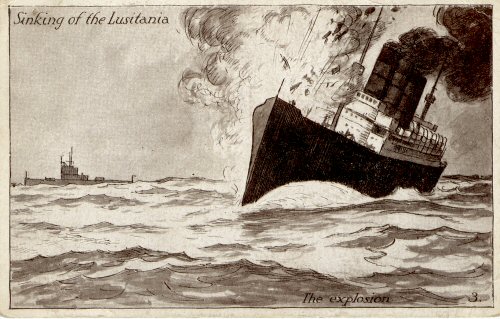

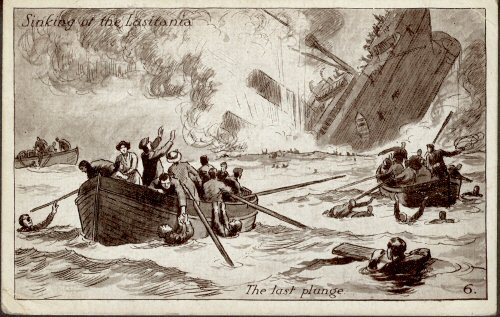

At 2.00pm the passengers were finishing their lunch, and at 2.15pm the ship was 10 to 15 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale with the weather clear and the sea smooth. Captain Turner then heard the second officer shout 'There is a torpedo coming, Sir'. Immediately afterwards there was a terrific explosion on the starboard side, between the third and fourth funnels. Almost simultaneously there was a second explosion, which was thought at the time to be a second torpedo but has since been confirmed as an internal explosion, although the cause has never been definitely established. The stricken Lusitania immediately took on a heavy list to starboard and in about 20 minutes it had sunk, with the loss of 1,198 lives. The ship sank bow first, with its stern almost perpendicular out of the water, just as the Titanic had done some 3 years earlier.

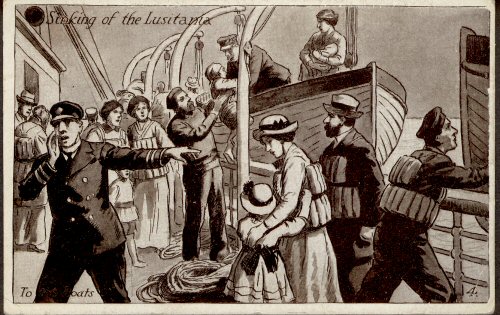

Captain Turner survived and he remained on the bridge giving orders until the ship foundered. His order 'women and children first' was largely obeyed. There were complaints from some of the survivors about the manner in which the lifeboats were launched, their condition and the lack of leadership from the ship's officers. But considering that within seconds of being hit all the lights went out and the ship listed heavily to starboard and that it remained under way the whole time, together with the fact that it sank in 18 minutes, it is a miracle that so many did get away safely.

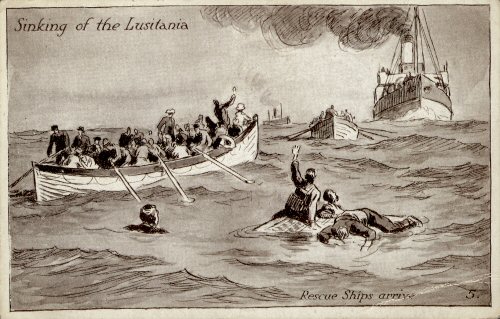

As always with such tragedies there were many stories of heroism, but two were officially recognised and Able Seamen Leslie Morton and Joseph Parry were awarded the silver and bronze medals for Gallantry in Saving Life at Sea. The citation to the awards read as follows - 'On 7th May 1915, the steamship Lusitania, of Liverpool, was torpedoed off the Old Head of Kinsale and foundered. Morton was the first to observe the approach of the torpedoes, and he reported them to the bridge. When the torpedoes struck the ship he was knocked off his feet, but he recovered himself quickly, and at once assisted in filling and lowering several boats. Having done all he could on board, he jumped overboard. While in the water he managed to get hold of a floating collapsible lifeboat and, with the assistance of Parry, he ripped the canvas cover off it and succeeded in drawing into it 50 or 60 passengers. Morton and Parry then rowed the boat some miles to a fishing smack. Having put the rescued passengers on board the smack they returned to the scene of the wreck and succeeded in rescuing 20 to 30 more people'.

There is no doubt that the sinking of the Lusitania was one of the First World War's single biggest tragedies. The political repercussions were enormous, and although it did not directly bring the United States into the War on the side of the Allies it ensured that no American administration would ever be allied to Germany.